71. Competitive Equilibria with Arrow Securities#

71.1. Introduction#

This lecture presents Python code for experimenting with competitive equilibria of an infinite-horizon pure exchange economy with

Heterogeneous agents

Endowments of a single consumption that are person-specific functions of a common Markov state

Complete markets in one-period Arrow state-contingent securities

Discounted expected utility preferences of a kind often used in macroeconomics and finance

Common expected utility preferences across agents

Common beliefs among agents

A constant relative risk aversion (CRRA) one-period utility function that implies the existence of a representative consumer whose consumption process can be plugged into a formula for the pricing kernel for one-step Arrow securities and thereby determine equilibrium prices before determining an equilibrium distribution of wealth

Differences in their endowments make individuals want to reallocate consumption goods across time and Markov states

We impose restrictions that allow us to Bellmanize competitive equilibrium prices and quantities

We use Bellman equations to describe

asset prices

continuation wealth levels for each person

state-by-state natural debt limits for each person

In the course of presenting the model we shall encounter these important ideas

a resolvent operator widely used in this class of models

absence of borrowing limits in finite horizon economies

state-by-state borrowing limits required in infinite horizon economies

a counterpart of the law of iterated expectations known as a law of iterated values

a state-variable degeneracy that prevails within a competitive equilibrium and that opens the way to various appearances of resolvent operators

71.2. The setting#

In effect, this lecture implements a Python version of the model presented in section 9.3.3 of Ljungqvist and Sargent [Ljungqvist and Sargent, 2018].

71.2.1. Preferences and endowments#

In each period

Let the history of events up until time

(Sometimes we inadvertently reverse the recording order and denote a history as

The unconditional

probability of observing a particular sequence of events

For

We assume that trading occurs after

observing

In this lecture we shall follow much macroeconomics and econometrics and assume that

There are

Consumer

The history

Consumer

Consumer

where

The right side is equal to

Here

The utility function of person

This condition implies that each

agent chooses strictly positive consumption for every

date-history pair

Those interior solutions enable us to confine our analysis to Euler equations that hold with equality and also guarantee that natural debt limits don’t bind in economies like ours with sequential trading of Arrow securities.

We adopt the assumption, routinely

employed in much of macroeconomics,

that consumers share probabilities

A feasible allocation satisfies

for all

71.3. Recursive Formulation#

Following descriptions in section 9.3.3 of Ljungqvist and Sargent [Ljungqvist and Sargent, 2018] chapter 9, we set up a competitive equilibrium of a pure exchange economy with complete markets in one-period Arrow securities.

When endowments

These enable us to provide a recursive formulation of a consumer’s optimization problem.

Consumer

Let

The optimal value function satisfies the Bellman equation

where maximization is subject to the budget constraint

and also the constraints

with the second constraint evidently being a set of state-by-state debt limits.

Note that the value function and decision rule that solve the Bellman equation implicitly depend

on the pricing kernel

Use the first-order conditions for the problem on the right of the Bellman equation and a Benveniste-Scheinkman formula and rearrange to get

where it is understood that

A recursive competitive equilibrium is

an initial distribution of wealth

The state-by-state borrowing constraints satisfy the recursion

For all

For all realizations of

The initial financial wealth vector

The third condition asserts that there are zero net aggregate claims in all Markov states.

The fourth condition asserts that the economy is closed and starts from a situation in which there are zero net aggregate claims.

71.4. State Variable Degeneracy#

Please see Ljungqvist and Sargent [Ljungqvist and Sargent, 2018] for a description of timing protocol for trades consistent with an Arrow-Debreu vision in which

at time

all trades occur once and for all at time

If an allocation and pricing kernel

That is

what assures that at time

Starting the system with

Here is what we mean by state variable degeneracy:

Although two state variables

Financial wealth

The first finding asserts that each household recurrently visits the zero financial wealth state with which it began life.

The second finding asserts that within a competitive equilibrium the exogenous Markov state is all we require to track an individual.

Financial wealth turns out to be redundant because it is an exact function of the Markov state for each individual.

This outcome depends critically on there being complete markets in Arrow securities.

For example, it does not prevail in the incomplete markets setting of this lecture The Aiyagari Model

71.5. Markov Asset Prices#

Let’s start with a brief summary of formulas for computing asset prices in a Markov setting.

The setup assumes the following infrastructure

Markov states:

A collection

An

The price of risk-free one-period bond in state

The gross rate of return on a one-period risk-free bond Markov state

71.5.1. Exogenous Pricing Kernel#

At this point, we’ll take the pricing kernel

Two examples would be

We’ll write down implications of Markov asset pricing in a nutshell for two types of assets

the price in Markov state

the price in Markov state

Note

The matrix geometric sum

Below, we describe an equilibrium model with trading of one-period Arrow securities in which the pricing kernel is endogenous.

In constructing our model, we’ll repeatedly encounter formulas that remind us of our asset pricing formulas.

71.5.2. Multi-Step-Forward Transition Probabilities and Pricing Kernels#

The

The

We’ll use these objects to state a useful property in asset pricing theory.

71.5.3. Laws of Iterated Expectations and Iterated Values#

A law of iterated values has a mathematical structure that parallels a law of iterated expectations

We can describe its structure readily in the Markov setting of this lecture

Recall the following recursion satisfied by

We can use this recursion to verify the law of iterated expectations applied

to computing the conditional expectation of a random variable

The pricing kernel for

The time

The law of iterated values states

We verify it by pursuing the following a string of inequalities that are counterparts to those we used to verify the law of iterated expectations:

71.6. General Equilibrium#

Now we are ready to do some fun calculations.

We find it interesting to think in terms of analytical inputs into and outputs from our general equilibrium theorizing.

71.6.1. Inputs#

Markov states:

A collection of

An

A collection of

A collection of restrictions on feasible consumption allocations for

Preferences: a common utility functional across agents

The one-period utility function is

so that

71.6.2. Outputs#

An

pure exchange so that

a

A collection of

71.6.3.

For any agent

where

This follows from agent

But with the CRRA preferences that we have assumed, individual consumptions vary proportionately with aggregate consumption and therefore with the aggregate endowment.

This is a consequence of our preference specification implying that Engle curves are affine in wealth and therefore satisfy conditions for Gorman aggregation

Thus,

for an arbitrary distribution of wealth in the form of an

This means that we can compute the pricing kernel from

Note that

Key finding: We can compute competitive equilibrium prices prior to computing a distribution of wealth.

71.6.4. Values#

Having computed an equilibrium pricing kernel

We denote an

and an

where

In a competitive equilibrium of an infinite horizon economy with sequential trading of one-period Arrow securities,

These are often called natural debt limits.

Evidently, they equal the maximum amount that it is feasible for individual

Remark: If we have an Inada condition at zero consumption or just impose that consumption be nonnegative, then in a finite horizon economy with sequential trading of one-period Arrow securities there is no need to impose natural debt limits. See the section on a Finite Horizon Economy below.

71.6.5. Continuation Wealth#

Continuation wealth plays an important role in Bellmanizing a competitive equilibrium with sequential trading of a complete set of one-period Arrow securities.

We denote an

and an

Continuation wealth

where

Note that

Remark: At the initial state

Remark: Note that all agents’ continuation wealths recurrently return to zero when the Markov state returns to whatever value

71.6.6. Optimal Portfolios#

A nifty feature of the model is that an optimal portfolio of a type

Thus, agent

71.6.7. Equilibrium Wealth Distribution

With the initial state being a particular state

which means the equilibrium distribution of wealth satisfies

where

Since

In summary, here is the logical flow of an algorithm to compute a competitive equilibrium:

compute

compute the distribution of wealth

Using

return to the

via formula (71.3) equate agent

We can also add formulas for optimal value functions in a competitive equilibrium with trades in a complete set of one-period state-contingent Arrow securities.

Call the optimal value functions

For the infinite horizon economy now under study, the formula is

where it is understood that

71.7. Finite Horizon#

We now describe a finite-horizon version of the economy that operates for

Consequently, we’ll want

borrowing limits aren’t required for a finite horizon economy in which a one-period utility function

Nonnegativity of consumption choices at all

71.7.1. Continuation Wealths#

We denote a

and an

Continuation wealths

where

Note that

Remark: At the initial state

Remark: Note that all agents’ continuation wealths return to zero when the Markov state returns to whatever value

With the initial state being a particular state

which means the equilibrium distribution of wealth satisfies

where now in our finite-horizon economy

and

Since

In summary, here is the logical flow of an algorithm to compute a competitive equilibrium with Arrow securities in our finite-horizon Markov economy:

compute

compute the distribution of wealth

using

return to the

equate agent

While for the infinite horizon economy, the formula for value functions is

for the finite horizon economy the formula is

where it is understood that

71.8. Python Code#

We are ready to dive into some Python code.

As usual, we start with Python imports.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

np.set_printoptions(suppress=True)

First, we create a Python class to compute the objects that comprise a competitive equilibrium with sequential trading of one-period Arrow securities.

In addition to infinite-horizon economies, the code is set up to handle finite-horizon economies indexed by horizon

We’ll study examples of finite horizon economies after we first look at some infinite-horizon economies.

class RecurCompetitive:

"""

A class that represents a recursive competitive economy

with one-period Arrow securities.

"""

def __init__(self,

s, # state vector

P, # transition matrix

ys, # endowments ys = [y1, y2, .., yI]

γ=0.5, # risk aversion

β=0.98, # discount rate

T=None): # time horizon, none if infinite

# preference parameters

self.γ = γ

self.β = β

# variables dependent on state

self.s = s

self.P = P

self.ys = ys

self.y = np.sum(ys, 1)

# dimensions

self.n, self.K = ys.shape

# compute pricing kernel

self.Q = self.pricing_kernel()

# compute price of risk-free one-period bond

self.PRF = self.price_risk_free_bond()

# compute risk-free rate

self.R = self.risk_free_rate()

# V = [I - Q]^{-1} (infinite case)

if T is None:

self.T = None

self.V = np.empty((1, n, n))

self.V[0] = np.linalg.inv(np.eye(n) - self.Q)

# V = [I + Q + Q^2 + ... + Q^T] (finite case)

else:

self.T = T

self.V = np.empty((T+1, n, n))

self.V[0] = np.eye(n)

Qt = np.eye(n)

for t in range(1, T+1):

Qt = Qt.dot(self.Q)

self.V[t] = self.V[t-1] + Qt

# natural debt limit

self.A = self.V[-1] @ ys

def u(self, c):

"The CRRA utility"

return c ** (1 - self.γ) / (1 - self.γ)

def u_prime(self, c):

"The first derivative of CRRA utility"

return c ** (-self.γ)

def pricing_kernel(self):

"Compute the pricing kernel matrix Q"

c = self.y

n = self.n

Q = np.empty((n, n))

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

ratio = self.u_prime(c[j]) / self.u_prime(c[i])

Q[i, j] = self.β * ratio * P[i, j]

self.Q = Q

return Q

def wealth_distribution(self, s0_idx):

"Solve for wealth distribution α"

# set initial state

self.s0_idx = s0_idx

# simplify notations

n = self.n

Q = self.Q

y, ys = self.y, self.ys

# row of V corresponding to s0

Vs0 = self.V[-1, s0_idx, :]

α = Vs0 @ self.ys / (Vs0 @ self.y)

self.α = α

return α

def continuation_wealths(self):

"Given α, compute the continuation wealths ψ"

diff = np.empty((n, K))

for k in range(K):

diff[:, k] = self.α[k] * self.y - self.ys[:, k]

ψ = self.V @ diff

self.ψ = ψ

return ψ

def price_risk_free_bond(self):

"Give Q, compute price of one-period risk free bond"

PRF = np.sum(self.Q, 0)

self.PRF = PRF

return PRF

def risk_free_rate(self):

"Given Q, compute one-period gross risk-free interest rate R"

R = np.sum(self.Q, 0)

R = np.reciprocal(R)

self.R = R

return R

def value_functionss(self):

"Given α, compute the optimal value functions J in equilibrium"

n, T = self.n, self.T

β = self.β

P = self.P

# compute (I - βP)^(-1) in infinite case

if T is None:

P_seq = np.empty((1, n, n))

P_seq[0] = np.linalg.inv(np.eye(n) - β * P)

# and (I + βP + ... + β^T P^T) in finite case

else:

P_seq = np.empty((T+1, n, n))

P_seq[0] = np.eye(n)

Pt = np.eye(n)

for t in range(1, T+1):

Pt = Pt.dot(P)

P_seq[t] = P_seq[t-1] + Pt * β ** t

# compute the matrix [u(α_1 y), ..., u(α_K, y)]

flow = np.empty((n, K))

for k in range(K):

flow[:, k] = self.u(self.α[k] * self.y)

J = P_seq @ flow

self.J = J

return J

71.9. Examples#

We’ll use our code to construct equilibrium objects in several example economies.

Our first several examples will be infinite horizon economies.

Our final example will be a finite horizon economy.

71.9.1. Example 1#

Please read the preceding class for default parameter values and the following Python code for the fundamentals of the economy.

Here goes.

# dimensions

K, n = 2, 2

# states

s = np.array([0, 1])

# transition

P = np.array([[.5, .5], [.5, .5]])

# endowments

ys = np.empty((n, K))

ys[:, 0] = 1 - s # y1

ys[:, 1] = s # y2

ex1 = RecurCompetitive(s, P, ys)

# endowments

ex1.ys

array([[1., 0.],

[0., 1.]])

# pricing kernal

ex1.Q

array([[0.49, 0.49],

[0.49, 0.49]])

# Risk free rate R

ex1.R

array([1.02040816, 1.02040816])

# natural debt limit, A = [A1, A2, ..., AI]

ex1.A

array([[25.5, 24.5],

[24.5, 25.5]])

# when the initial state is state 1

print(f'α = {ex1.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=0)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex1.continuation_wealths()}')

print(f'J = \n{ex1.value_functionss()}')

α = [0.51 0.49]

ψ =

[[[ 0. -0.]

[ 1. -1.]]]

J =

[[[71.41428429 70. ]

[71.41428429 70. ]]]

# when the initial state is state 2

print(f'α = {ex1.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=1)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex1.continuation_wealths()}')

print(f'J = \n{ex1.value_functionss()}')

α = [0.49 0.51]

ψ =

[[[-1. 1.]

[ 0. -0.]]]

J =

[[[70. 71.41428429]

[70. 71.41428429]]]

71.9.2. Example 2#

# dimensions

K, n = 2, 2

# states

s = np.array([1, 2])

# transition

P = np.array([[.5, .5], [.5, .5]])

# endowments

ys = np.empty((n, K))

ys[:, 0] = 1.5 # y1

ys[:, 1] = s # y2

ex2 = RecurCompetitive(s, P, ys)

# endowments

print("ys = \n", ex2.ys)

# pricing kernal

print ("Q = \n", ex2.Q)

# Risk free rate R

print("R = ", ex2.R)

ys =

[[1.5 1. ]

[1.5 2. ]]

Q =

[[0.49 0.41412558]

[0.57977582 0.49 ]]

R = [0.93477529 1.10604104]

# pricing kernal

ex2.Q

array([[0.49 , 0.41412558],

[0.57977582, 0.49 ]])

Note that the pricing kernal in example economies 1 and 2 differ.

This comes from differences in the aggregate endowments in state 1 and 2 in example 1.

ex2.β * ex2.u_prime(3.5) / ex2.u_prime(2.5) * ex2.P[0,1]

0.4141255848169731

ex2.β * ex2.u_prime(2.5) / ex2.u_prime(3.5) * ex2.P[1,0]

0.5797758187437624

# Risk free rate R

ex2.R

array([0.93477529, 1.10604104])

# natural debt limit, A = [A1, A2, ..., AI]

ex2.A

array([[69.30941886, 66.91255848],

[81.73318641, 79.98879094]])

# when the initial state is state 1

print(f'α = {ex2.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=0)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex2.continuation_wealths()}')

print(f'J = \n{ex2.value_functionss()}')

α = [0.50879763 0.49120237]

ψ =

[[[-0. -0. ]

[ 0.55057195 -0.55057195]]]

J =

[[[122.907875 120.76397493]

[123.32114686 121.17003803]]]

# when the initial state is state 1

print(f'α = {ex2.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=1)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex2.continuation_wealths()}')

print(f'J = \n{ex2.value_functionss()}')

α = [0.50539319 0.49460681]

ψ =

[[[-0.46375886 0.46375886]

[ 0. -0. ]]]

J =

[[[122.49598809 121.18174895]

[122.907875 121.58921679]]]

71.9.3. Example 3#

# dimensions

K, n = 2, 2

# states

s = np.array([1, 2])

# transition

λ = 0.9

P = np.array([[1-λ, λ], [0, 1]])

# endowments

ys = np.empty((n, K))

ys[:, 0] = [1, 0] # y1

ys[:, 1] = [0, 1] # y2

ex3 = RecurCompetitive(s, P, ys)

# endowments

print("ys = ", ex3.ys)

# pricing kernel

print ("Q = ", ex3.Q)

# Risk free rate R

print("R = ", ex3.R)

ys = [[1. 0.]

[0. 1.]]

Q = [[0.098 0.882]

[0. 0.98 ]]

R = [10.20408163 0.53705693]

# pricing kernel

ex3.Q

array([[0.098, 0.882],

[0. , 0.98 ]])

# natural debt limit, A = [A1, A2, ..., AI]

ex3.A

array([[ 1.10864745, 48.89135255],

[ 0. , 50. ]])

Note that the natural debt limit for agent

# when the initial state is state 1

print(f'α = {ex3.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=0)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex3.continuation_wealths()}')

print(f'J = \n{ex3.value_functionss()}')

α = [0.02217295 0.97782705]

ψ =

[[[ 0. -0. ]

[ 1.10864745 -1.10864745]]]

J =

[[[14.89058394 98.88513796]

[14.89058394 98.88513796]]]

# when the initial state is state 1

print(f'α = {ex3.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=1)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex3.continuation_wealths()}')

print(f'J = \n{ex3.value_functionss()}')

α = [0. 1.]

ψ =

[[[-1.10864745 1.10864745]

[ 0. 0. ]]]

J =

[[[ 0. 100.]

[ 0. 100.]]]

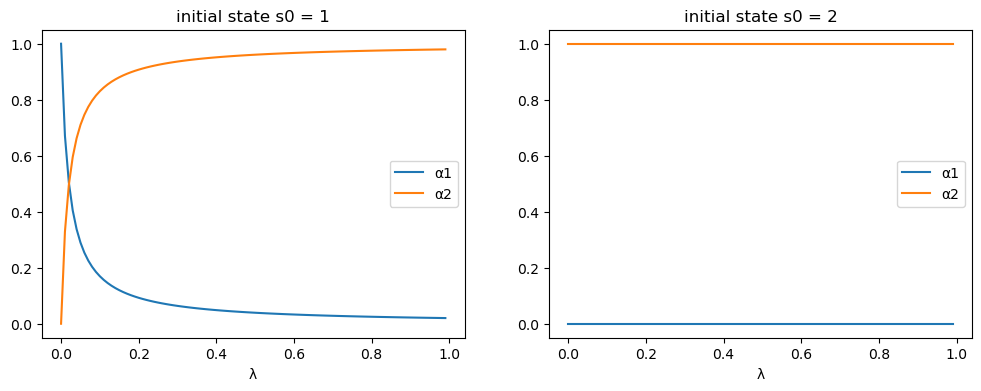

For the specification of the Markov chain in example 3, let’s take a look at how the equilibrium allocation changes as a function of transition probability

λ_seq = np.linspace(0, 0.99, 100)

# prepare containers

αs0_seq = np.empty((len(λ_seq), 2))

αs1_seq = np.empty((len(λ_seq), 2))

for i, λ in enumerate(λ_seq):

P = np.array([[1-λ, λ], [0, 1]])

ex3 = RecurCompetitive(s, P, ys)

# initial state s0 = 1

α = ex3.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=0)

αs0_seq[i, :] = α

# initial state s0 = 2

α = ex3.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=1)

αs1_seq[i, :] = α

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

for i, αs_seq in enumerate([αs0_seq, αs1_seq]):

for j in range(2):

axs[i].plot(λ_seq, αs_seq[:, j], label=f'α{j+1}')

axs[i].set_xlabel('λ')

axs[i].set_title(f'initial state s0 = {s[i]}')

axs[i].legend()

plt.show()

71.9.4. Example 4#

# dimensions

K, n = 2, 3

# states

s = np.array([1, 2, 3])

# transition

λ = .9

μ = .9

δ = .05

# prosperous, moderate, and recession states

P = np.array([[1-λ, λ, 0], [μ/2, μ, μ/2], [(1-δ)/2, (1-δ)/2, δ]])

# endowments

ys = np.empty((n, K))

ys[:, 0] = [.25, .75, .2] # y1

ys[:, 1] = [1.25, .25, .2] # y2

ex4 = RecurCompetitive(s, P, ys)

# endowments

print("ys = \n", ex4.ys)

# pricing kernal

print ("Q = \n", ex4.Q)

# Risk free rate R

print("R = ", ex4.R)

# natural debt limit, A = [A1, A2, ..., AI]

print("A = \n", ex4.A)

print('')

for i in range(1, 4):

# when the initial state is state i

print(f"when the initial state is state {i}")

print(f'α = {ex4.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=i-1)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex4.continuation_wealths()}')

print(f'J = \n{ex4.value_functionss()}\n')

ys =

[[0.25 1.25]

[0.75 0.25]

[0.2 0.2 ]]

Q =

[[0.098 1.08022498 0. ]

[0.36007499 0.882 0.69728222]

[0.24038317 0.29440805 0.049 ]]

R = [1.43172499 0.44313807 1.33997564]

A =

[[-1.4141307 -0.45854174]

[-1.4122483 -1.54005386]

[-0.58434331 -0.3823659 ]]

when the initial state is state 1

α = [0.75514045 0.24485955]

ψ =

[[[ 0. 0. ]

[-0.81715447 0.81715447]

[-0.14565791 0.14565791]]]

J =

[[[-2.65741909 -1.51322919]

[-5.13103133 -2.92179221]

[-2.65649938 -1.51270548]]]

when the initial state is state 2

α = [0.47835493 0.52164507]

ψ =

[[[ 0.5183286 -0.5183286 ]

[ 0. -0. ]

[ 0.12191319 -0.12191319]]]

J =

[[[-2.11505328 -2.20868477]

[-4.08381377 -4.26460049]

[-2.11432128 -2.20792037]]]

when the initial state is state 3

α = [0.60446648 0.39553352]

ψ =

[[[ 0.28216299 -0.28216299]

[-0.37231938 0.37231938]

[ 0. -0. ]]]

J =

[[[-2.37756442 -1.92325926]

[-4.59067883 -3.71349163]

[-2.37674158 -1.92259365]]]

71.9.5. Finite Horizon Example#

We now revisit the economy defined in example 1, but set the time horizon to be

# dimensions

K, n = 2, 2

# states

s = np.array([0, 1])

# transition

P = np.array([[.5, .5], [.5, .5]])

# endowments

ys = np.empty((n, K))

ys[:, 0] = 1 - s # y1

ys[:, 1] = s # y2

ex1_finite = RecurCompetitive(s, P, ys, T=10)

# (I + Q + Q^2 + ... + Q^T)

ex1_finite.V[-1]

array([[5.48171623, 4.48171623],

[4.48171623, 5.48171623]])

# endowments

ex1_finite.ys

array([[1., 0.],

[0., 1.]])

# pricing kernal

ex1_finite.Q

array([[0.49, 0.49],

[0.49, 0.49]])

# Risk free rate R

ex1_finite.R

array([1.02040816, 1.02040816])

In the finite time horizon case, ψ and J are returned as sequences.

Components are ordered from

# when the initial state is state 2

print(f'α = {ex1_finite.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=0)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex1_finite.continuation_wealths()}\n')

print(f'J = \n{ex1_finite.value_functionss()}')

α = [0.55018351 0.44981649]

ψ =

[[[-0.44981649 0.44981649]

[ 0.55018351 -0.55018351]]

[[-0.40063665 0.40063665]

[ 0.59936335 -0.59936335]]

[[-0.35244041 0.35244041]

[ 0.64755959 -0.64755959]]

[[-0.30520809 0.30520809]

[ 0.69479191 -0.69479191]]

[[-0.25892042 0.25892042]

[ 0.74107958 -0.74107958]]

[[-0.21355851 0.21355851]

[ 0.78644149 -0.78644149]]

[[-0.16910383 0.16910383]

[ 0.83089617 -0.83089617]]

[[-0.12553824 0.12553824]

[ 0.87446176 -0.87446176]]

[[-0.08284397 0.08284397]

[ 0.91715603 -0.91715603]]

[[-0.04100358 0.04100358]

[ 0.95899642 -0.95899642]]

[[-0. -0. ]

[ 1. -1. ]]]

J =

[[[ 1.48348712 1.3413672 ]

[ 1.48348712 1.3413672 ]]

[[ 2.9373045 2.65590706]

[ 2.9373045 2.65590706]]

[[ 4.36204553 3.94415611]

[ 4.36204553 3.94415611]]

[[ 5.75829174 5.20664019]

[ 5.75829174 5.20664019]]

[[ 7.12661302 6.44387459]

[ 7.12661302 6.44387459]]

[[ 8.46756788 7.6563643 ]

[ 8.46756788 7.6563643 ]]

[[ 9.78170364 8.84460421]

[ 9.78170364 8.84460421]]

[[11.06955669 10.00907933]

[11.06955669 10.00907933]]

[[12.33165268 11.15026494]

[12.33165268 11.15026494]]

[[13.56850674 12.26862684]

[13.56850674 12.26862684]]

[[14.78062373 13.3646215 ]

[14.78062373 13.3646215 ]]]

# when the initial state is state 2

print(f'α = {ex1_finite.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=1)}')

print(f'ψ = \n{ex1_finite.continuation_wealths()}\n')

print(f'J = \n{ex1_finite.value_functionss()}')

α = [0.44981649 0.55018351]

ψ =

[[[-0.55018351 0.55018351]

[ 0.44981649 -0.44981649]]

[[-0.59936335 0.59936335]

[ 0.40063665 -0.40063665]]

[[-0.64755959 0.64755959]

[ 0.35244041 -0.35244041]]

[[-0.69479191 0.69479191]

[ 0.30520809 -0.30520809]]

[[-0.74107958 0.74107958]

[ 0.25892042 -0.25892042]]

[[-0.78644149 0.78644149]

[ 0.21355851 -0.21355851]]

[[-0.83089617 0.83089617]

[ 0.16910383 -0.16910383]]

[[-0.87446176 0.87446176]

[ 0.12553824 -0.12553824]]

[[-0.91715603 0.91715603]

[ 0.08284397 -0.08284397]]

[[-0.95899642 0.95899642]

[ 0.04100358 -0.04100358]]

[[-1. 1. ]

[-0. -0. ]]]

J =

[[[ 1.3413672 1.48348712]

[ 1.3413672 1.48348712]]

[[ 2.65590706 2.9373045 ]

[ 2.65590706 2.9373045 ]]

[[ 3.94415611 4.36204553]

[ 3.94415611 4.36204553]]

[[ 5.20664019 5.75829174]

[ 5.20664019 5.75829174]]

[[ 6.44387459 7.12661302]

[ 6.44387459 7.12661302]]

[[ 7.6563643 8.46756788]

[ 7.6563643 8.46756788]]

[[ 8.84460421 9.78170364]

[ 8.84460421 9.78170364]]

[[10.00907933 11.06955669]

[10.00907933 11.06955669]]

[[11.15026494 12.33165268]

[11.15026494 12.33165268]]

[[12.26862684 13.56850674]

[12.26862684 13.56850674]]

[[13.3646215 14.78062373]

[13.3646215 14.78062373]]]

We can check the results with finite horizon converges to the ones with infinite horizon as

ex1_large = RecurCompetitive(s, P, ys, T=10000)

ex1_large.wealth_distribution(s0_idx=1)

array([0.49, 0.51])

ex1.V, ex1_large.V[-1]

(array([[[25.5, 24.5],

[24.5, 25.5]]]),

array([[25.5, 24.5],

[24.5, 25.5]]))

ex1_large.continuation_wealths()

ex1.ψ, ex1_large.ψ[-1]

(array([[[-1., 1.],

[ 0., -0.]]]),

array([[-1., 1.],

[ 0., -0.]]))

ex1_large.value_functionss()

ex1.J, ex1_large.J[-1]

(array([[[70. , 71.41428429],

[70. , 71.41428429]]]),

array([[70. , 71.41428429],

[70. , 71.41428429]]))